Sue Barr, one of Photocrowd's Expert Judges, on the purpose and challenges of photographing Italian motorways.

As an architectural photographer I tend to work on small-scale experimental projects, and I am fortunate to frequently find myself shooting contemporary architecture in some very fine locations.

One of my favourite commissions was the one I did for the award-winning London architects Tonkin Liu, who have converted a penthouse of a listed beaux-arts mansion block into an almost entirely white, extremely minimalist apartment with sliding walls, exquisite detailing and amazing views over central London.

This privilege of shooting in such beautiful locations is in stark contrast with the PhD research project I am now completing.

In my previous personal projects, as well as when I was an art student at the London College of Printing (as it was then called), I have always had a rather unhealthy obsession with concrete, and the more brutal the concrete the better.

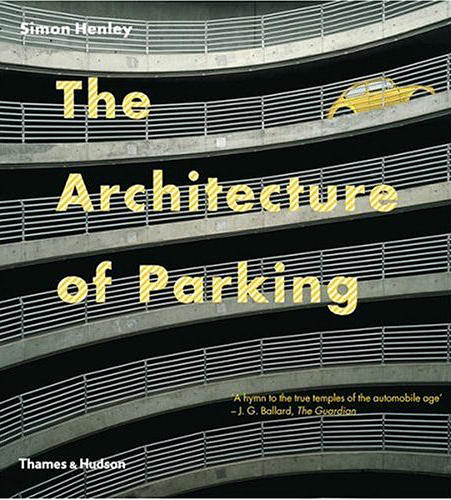

I spent years trawling through the insalubrious architecture of multi-storey car parks, making a series of photographs. Eventually these were published - in collaboration with the architect and fellow car park enthusiast Simon Henley - in a book entitled The Architecture of Parking. Much to our surprise, it even won some awards.

Five years ago I enrolled at the Royal College of Art in London to undertake a PhD project in which I use digital photography to investigate the often-ignored architecture of motorways.

The normal response I receive when I tell people what I’m researching is: “Why on earth are you interested in motorways? They are so boring!”

Well, yes and no.

In Britain, because the landscape topography isn’t extreme, the motorways are less dramatic than in Europe, especially in Switzerland and Italy, where my research project is based. Over there, road architecture is often heroic, particularly where the motorway is traversing mountain ranges or negotiating over and through a dense city.

So in theory I have a strangely photogenic research subject of motorway architecture, but in reality this is where the difficulties begin.

Finding an appropriate place to assemble my tripod and camera and compose the photograph is extremely difficult.

Before going on a location shoot I spend weeks pouring over detailed maps of the area and consulting Google Earth for possible street views; trying to work out when the sun will shine on a particular elevation, or when shadows might potentially obstruct a viewpoint.

Then, when I’m at the location I spend hours driving back and forth the same stretch of minor road, searching for vantage points from which to shoot. And I’m always far too slow for my fellow drivers attempting to reach hyper speed behind me.

Sometimes, when the location where I want to shoot is in a city, it is necessary to get up very early. This was particularly true when I was shooting motorways that encircle Naples. As photographers, we all know that the best light of the day is usually in the early morning and Neapolitan light is no exception. After about 11am the light is too hazy and looses its effect of sharpening clarity. Plus the intense heat of an Italian summer makes hard work out of the simplest things, let alone of spending prolonged amounts of time under a black focusing cloth.

Another reason for an early morning start is the curiosity that photography can arouse when shooting in unusual non-touristic locations: “Che cosa fai?” is a common question I hear from confused locals, who understandably have no interest in their neighbouring motorways.

I use a Silvestri camera and Phase One digital back, but I also drag around a large step ladder and a box of lenses, filters etc. So I’m hardly inconspicuous when shooting.

Although luckily, the strangeness of my camera combined with a wooden Berlebach tripod make me look more like a Victorian photographer, or my hero the American photographer Timothy O’Sullivan, than a potentially muggable tourist with an expensive DSLR.

One of my favourite photographs from the Naples series was shot at 4.30am. My assistant and I had scouted out the location the previous afternoon on a “drive-by shooting” for potential photographs. But what I hadn’t particularly noticed were the mountains of rubbish - old mattresses and unidentifiable liquids – and the peculiar odours they were emitting. These mountains of rubbish were located exactly where I would need to assemble my tripod.

So when we returned there the next morning to shoot, I quickly realised that the shorts and sneakers I was wearing were not a sensible sartorial choice. I longed for the work boots and the indestructible Carhartt trousers I normally wear when photographing on construction sites back in the UK.

The fact that composing photographs on a ground glass viewfinder is a very slow process did not help matters when huge lorries were thundering past, sounding their horns as soon as they noticed the camera.

At that point the elegant apartments and exquisite architectures from my life as a commercial photographer felt a million miles away.

The aim of my motorway photographs was to illustrate the sublime qualities - in the original 18th century sense of the word - of both the decaying architecture and the intensity of the Neapolitan light.

I managed to photograph the architecture with the beautiful early morning light and shadow dissecting the composition, directly below the motorway - exactly where I had hoped the shadow would fall. So the flea bites I received were a small price to pay.

Later, on my return to the hotel, and after checking the photographs on my laptop, I was ready for a Campari aperitivo. Just to anaesthetise the flea bites, of course.

Enter Photocrowd's photo contests to win great prizes.

Register on Photocrowd for more great content.