The Lancashire-born master of minimalism has spent years honing his approach to landscapes. We take a look at how he captures his unique vision of the world

Namyeong Lion Rock, Mongdol Beach, Jeollanam-do, South Korea. 2018

Embrace minimalism

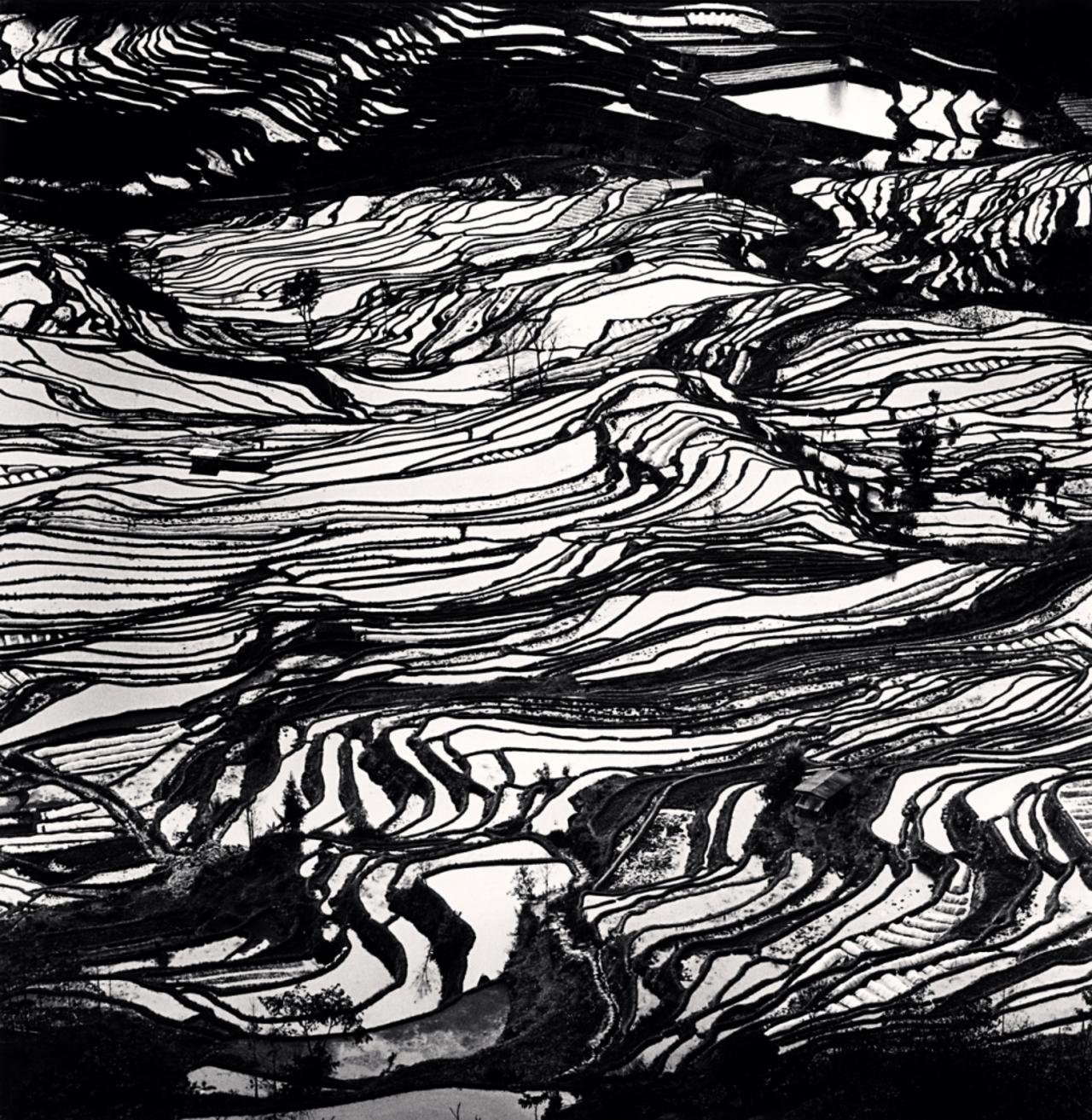

Minimalism is the key word when discussing Kenna’s work. Look through Kenna’s images and you can see he rarely shoots busy and chaotic scenes. His images are simple and quiet, empty but for the bare minimum of visual elements. He allows the scene to speak for itself and embraces a Zen-like approach to image making.

‘Patterns, shapes, and graphics attract me,’ says Kenna. ‘Drama, atmosphere, mystery, beauty. Elements, weather conditions, movement. Character, memories, traces. It's a matter of personal connection and resonance.’

Kussharo Lake Tree, Study 4, Kotan, Hokkaido, Japan. 2007

Shoot with film

While Kenna shoots his commercial work with digital cameras, he has become renowned for the fact he shoots all his personal work on medium format Hasselblad 500CM film cameras. Digital photography is a fantastic and accessible format but it can sometimes mean we lose some crucial factors that are part of film’s charm, most notably the slowness, unpredictability and the complications that arise when using an analogue format.

Shooting with film requires that you take your time meditating upon the scene and ensuring you achieve exactly the right exposure. It forces you to study the light and the conditions of the scene. Shooting film also means you are restricted to the number of frames per film and how many rolls of films you have on you. That means there’s no room for error.

Sapir Docks, Study 2, Ravenna, Italy, 2010

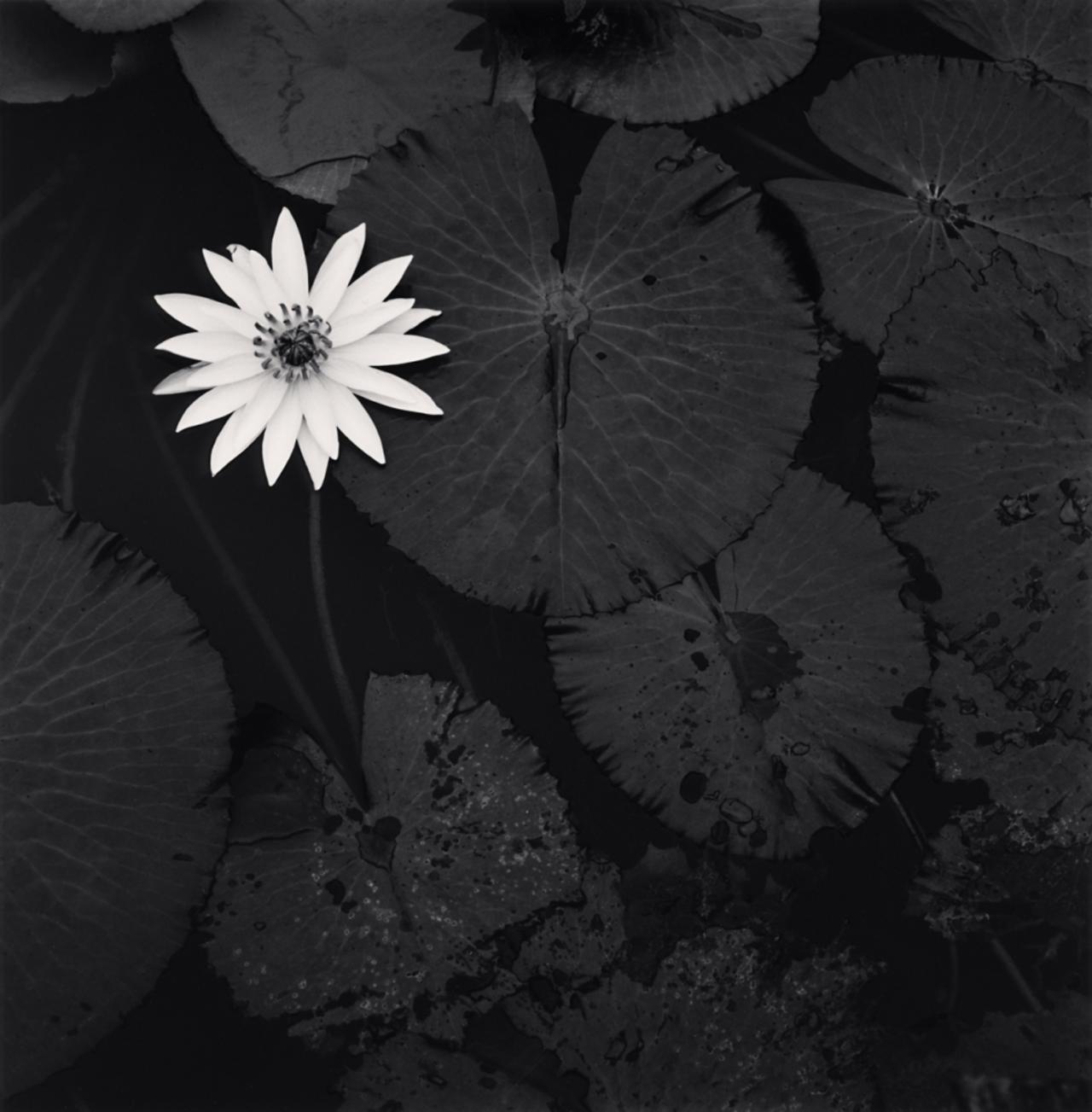

Shoot in black & white

Asides from his use of film, Kenna is perhaps most famous for his use of black & white. This is crucial for the minimalist aesthetic Kenna is searching for. Kenna uses the metaphor of haiku poetry – just a few words suggest an enormous world. Less information offers the viewer more room for imagination. By removing the colours of a scene, Kenna is able to remove one more distraction from the image.

Mamta's Lotus Flower, Ban Viengkeo, Luang Prabang, Laos. 2015

Shoot in square format

Shooting in square format is a result of the 6x6 and 6x4.5 film that Kenna uses in his Hasselblad cameras. This links back to the previous idea of simplifying the scene. A square is a clean, simple shape. Shooting square format alters the way you see the scene. It shifts your relationship to framing and how you present forms, lines and shapes within a landscape (or whatever genre you choose to work in). If you’re shooting digital, it’s worth experimenting with changing your camera’s aspect ratio (consult your camera’s manual for how to do this) and seeing how your reaction to composition shifts.

Also note that, while you can shoot a more rectangle format and crop late in post-production, it can generate better results if you aim to get it right in-camera.

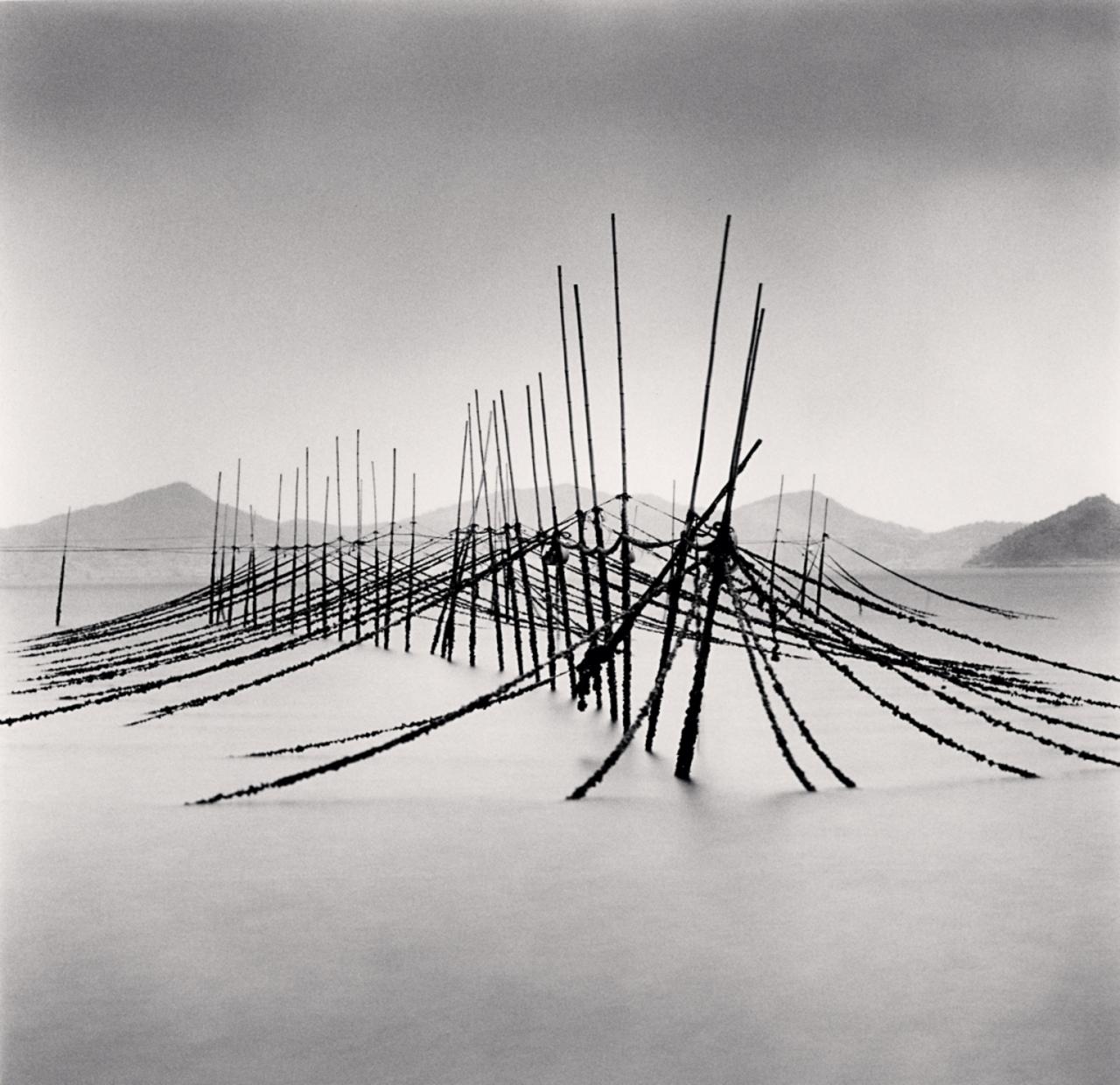

Aquaculture Structure, Boseong, Jeollanam-do, South Korea. 2018

Carry a range of lenses

While it’s always nice to set yourself some restrictions by carrying just one or two lenses with you to a shoot, it’s worth borrowing a couple of extra lenses and experimenting with a range of focal lengths to see how each can interpret a scene differently. Kenna tends to travel with lenses ranging from 40mm to 250mm and selects each one according to his needs. Again, we see how important it is to take your time studying a location. Spend a while attaching each lens to your camera and look at what each one does for a location.

Thirty One Snow Fences, Bihoro, Hokkaido, Japan. 2016

Work in all types of weather

As any serious landscape photographer knows, bad weather is no excuse to stay indoors. Kenna shoots whether it’s overcast, rainy, snowy or misty. In fact, these conditions only serve to emphasise the dreamy feeling of Kenna’s images. Conditions such as rain and mist reduce the scene down and draw attention to the vital elements of the composition.

Frozen Fountain, Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan, USA, 1994

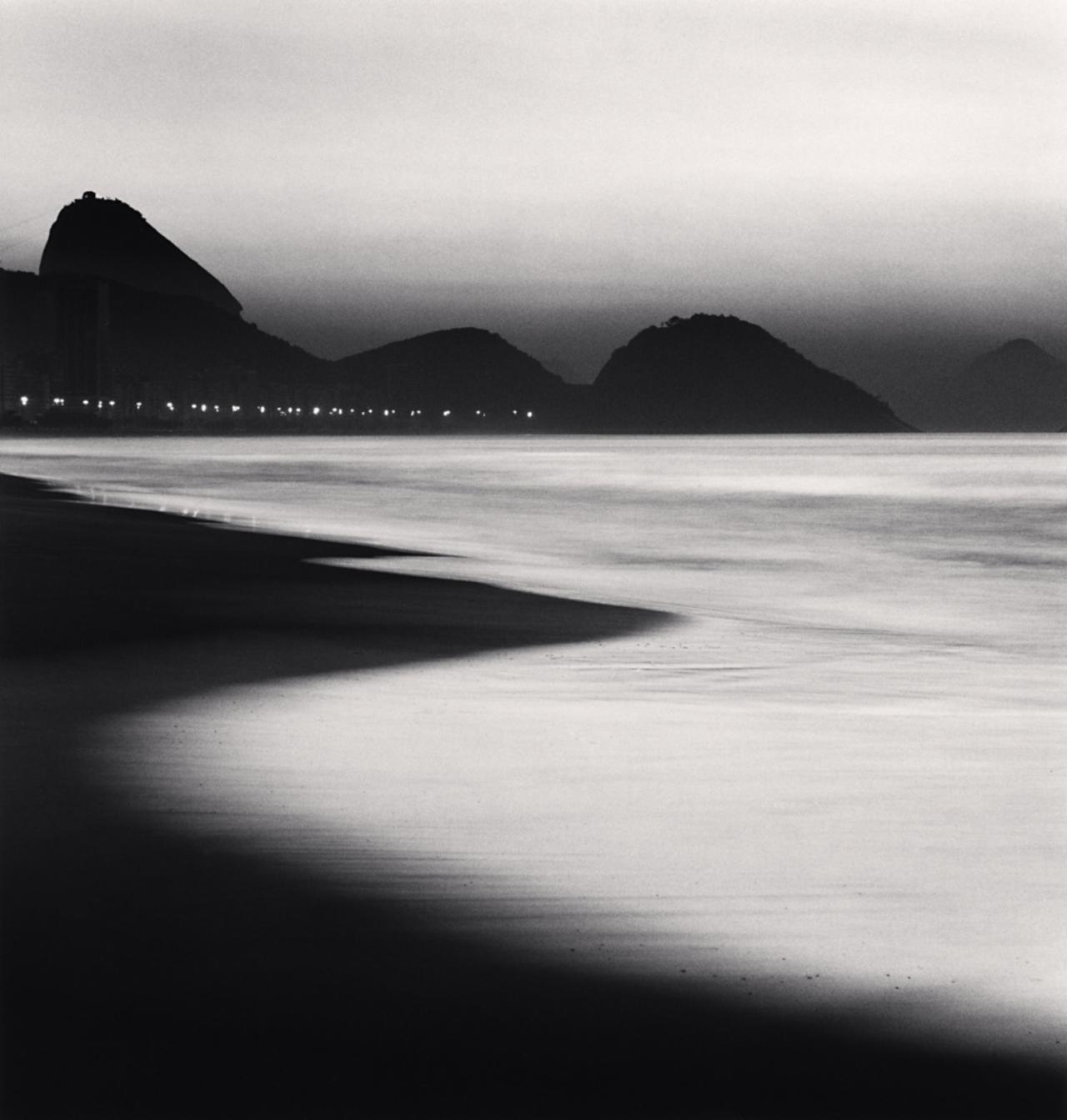

Shoot early morning and at night

Kenna’s images are infused with feelings of isolation, calm, and perhaps even a little alienation. Part of this is due to the fact that people very rarely feature in Kenna’s work and that’s because he’s often shooting in a) remote locations, and b) at those times of day when people are often asleep. (add ref to the fact that if using long shutter speeds, moving objects won’t show up. If this is how he shoots) Shooting in the very early morning or late at night means Kenna can shoot scenes undisturbed and untroubled by human presence. Locations take on a magical atmosphere at these times. Early morning mist is a particularly good example of this idea.

Yedang Reservoir Tree, Chungcheongnam-do, South Korea. 2018

Shoot long exposures

Long exposures have been a key feature of Kenna’s work for many years.

‘During a long exposure, the world changes,’ says Kenna. ‘Rivers flow, planes fly by, clouds pass and the Earth’s position relative to the stars is different. This accumulation of light, time and movement, impossible for the human eye to take in, can be recorded on film. Real becomes surreal, which is wonderful.’

Kenna’s work can often feature water and shooting long exposures means he can reduce the water to a glassy surface. However, if you’re really looking to have a go at recreating Kenna’s work, then be prepared for some seriously long exposures. Some of his take up to 12 hours to achieve. The added benefit of this, however, is that moving images will definitely not show up in the frame.

Carnegie Hall and CitySpire Center, New York, New York, USA. 2010

Use filters

If you’re looking to try your hand at long exposures, then you’ll be wise to invest in neutral density filters, as Kenna has. Your choice of filter (3-stop, 6-stop, 10-stop, etc.) will be determined by how long you want your exposure, so think about that first. Each additional stop will double the length of the exposure.

In addition to neutral density filters, Kenna also uses red or orange filters to change the contrast and tonality of his images.

Copacabana Beach, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. 2006

Experiment with different types of cameras

Kenna doesn’t always use Hasselblad cameras. Sometimes he experiments with Holga cameras, too. This is an interesting point to raise as it’s a clear demonstration of how your choice of camera should actually be fairly low down on your list of priorities. Despite working with a plastic toy camera, Kenna is still able to achieve images that are technically brilliant and full of atmosphere. What counts most is the location, the composition and the atmosphere.

From Kenna's 2017 publication, 'Holga'.

Learn to see the beauty in the everyday

It wouldn’t be unfair to say there’s nothing essentially extraordinary about the locations in which Kenna works. You could almost say they’re fairly nondescript. But that’s the point. Rather than shooting awe-inspiring locations, Kenna instead chooses to visit areas that many photographers would perhaps overlook due to their ordinariness. Through the sheer act of photographing them, he reveals the hidden beauty of everyday locations. The next time you’re out, keep your eyes open for those locations that can so often be missed. The more ordinary, the better.

Morning Traffic, Midtown, New York City, USA, 2000

Don’t go in with preconceived ideas

One of Kenna’s favourite quotes, and something of a personal philosophy, comes from photographer Garry Winogrand: ‘Photograph to see what something looks like photographed.’

Kenna resists making specific, conscious decisions ahead of time and instead allows the location to dictate the photograph.

‘For me, approaching subject matter to photograph is a bit like meeting a person and beginning a conversation,’ says Kenna. ‘How do I know ahead of time where that will lead? Curiosity is important. So is a willingness to be patient, to allow a subject matter to reveal itself.’

The Rouge, Study 133, Dearborn, Michigan, USA. 1995

Keep going back

It can often be the case that you don’t always get what you want the first time around. It can also be the case that you get some great images but feel the location still has much to offer. That’s why you must visit a location on more than one occasion. Kenna has visited Japan several times in a 30-year period, particularly the area of Hokkaido. Each of the images, all of which were taken at different times, work independently and tell you something new about the location. You never get a sense that Kenna is showing you something you’ve already seen.

Yuanyang, Study 3, Yunnan, China. 2013