Anthony Luvera on challenging societal preconceptions through self-portraiture and how the genre can still be relevant in the age of the 'selfie'.

Photographer Anthony Luvera was Photocrowd's Expert Judge in our recent self-portrait assignment, and we highly recommend reading his brilliant and in-depth reviews of his favourite images from the assignment. Below is our interview with Anthony, in which we ask him about his artistic exploration of social issues through portraiture and self-portraiture.

Tell us about your background in photography. How did you get into it?

I began getting into photography when I was a teenager living in Perth, Western Australia. My best mate and I taught ourselves how to use SLR cameras and we set up a darkroom in the bathroom of his family home. After a short time we advertised photography courses in the local newspaper. We had these rather confused-looking adults arriving at the house expecting to be taught by much older photographers than us!

A few years later I enrolled at university to study English Literature and Media and Communications. As part of the media studies course I took a unit in photography and quickly realised that I needed to refocus all of what I was doing to center entirely on creating photography and writing.

After my studies I began working as a fashion and portrait photographer before moving to London in 1999. Around 2001/02 I began working with homeless people and became more interested in collaboration, and this has since formed the backbone of my photographic practice as it is now.

What keeps you engaged with photography?

I think about photographs, look at images and talk about photography literally all the time. It feels like a natural persuasion or some kind of dementia! I think the wonderful thing about the medium is that it is in a continual state of reinvention and so there are always new technologies to learn, other people's perspectives to consider, as well as different and often surprising contexts to view photographs in. Teaching photography is also very inspiring for me. There's something about being involved in other people's enthusiasm for photography that feeds my own excitement about photographs.

What makes self-portraiture different from regular portraiture? What are the main

challenges in either genre?

All photographs tell stories and all photographers are storytellers. I think self-portraiture can be most exciting when it is seen as a lens through which to consider broader social, political or cultural issues, and when it's not simply a representation of identity, physiology or psychology of an individual. Some recent artists who have produced what I think are very interesting examples of this include Andre Penteado, Leigh Ledare, Trish Morrissey, Christian Thompson and Danny Treacy. Each of these artists creates self-portraits in ways that encourage us to think more deeply about more than who they are.

What are you favourite examples of self-portraiture in art as well as photography?

I particularly like the sculpture called 'Self' by Marc Quin held in the National Portrait Gallery, which was created with the artist's frozen blood. It's a marvelous idea and a compelling piece to look at. And I've always thought of the stencil paintings of Indigenous Australian people as a kind of self-portraiture and I find these images endlessly intriguing.

Tell us about your project assisting homeless people in photographing themselves. What were your main goals?

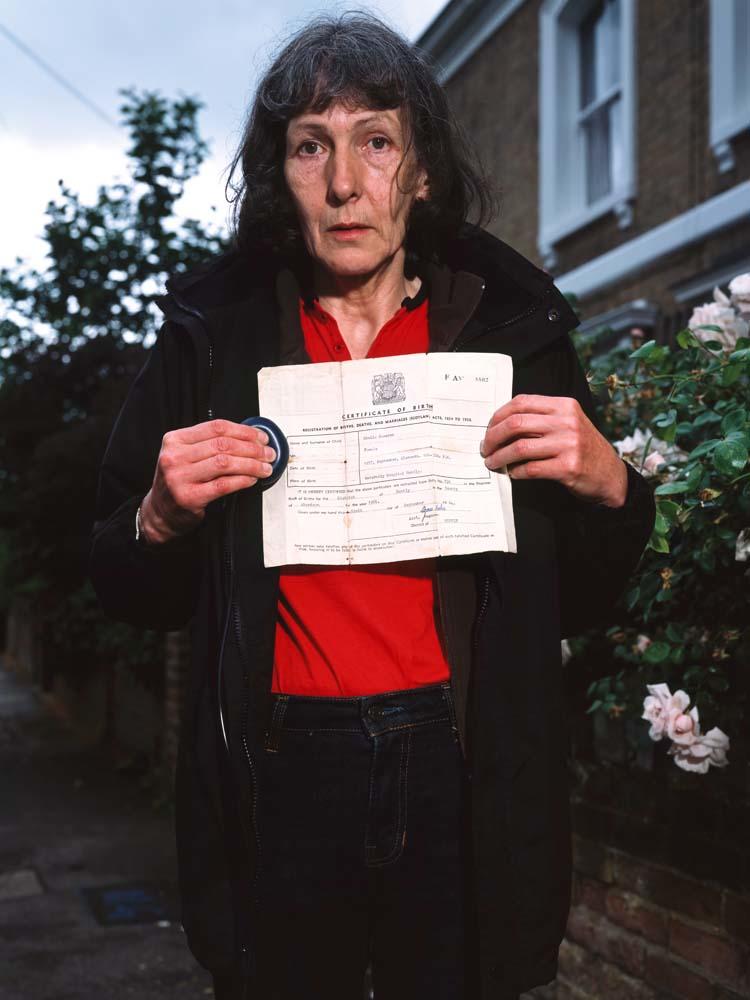

At the end of 2001 someone working for the homeless charity Crisis suggested that I get involved with their shelter event 'Crisis Open Christmas' by photographing homeless people. I remarked that I'd prefer to see what the people I met would photograph rather than photograph them myself. A short while later I sought sponsorship from Kodak and I began hosting drop-in sessions where I encouraged people to photograph the things that interested them and to share the images with me if they wanted to. I also began teaching participants to use large-format camera equipment to create what I call Assisted Self-Portraits. Through this work and the other projects I have created my intention has been to explore the perspectives of the people I work with and to find ways to present this alongside mine. With all of my work I hope that it may go some way to shaking up people's preconceptions about issues related to what it depicts.

Can you elaborate on the term ‘assisted’? How much say did the subjects have in post-processing/final presentation?

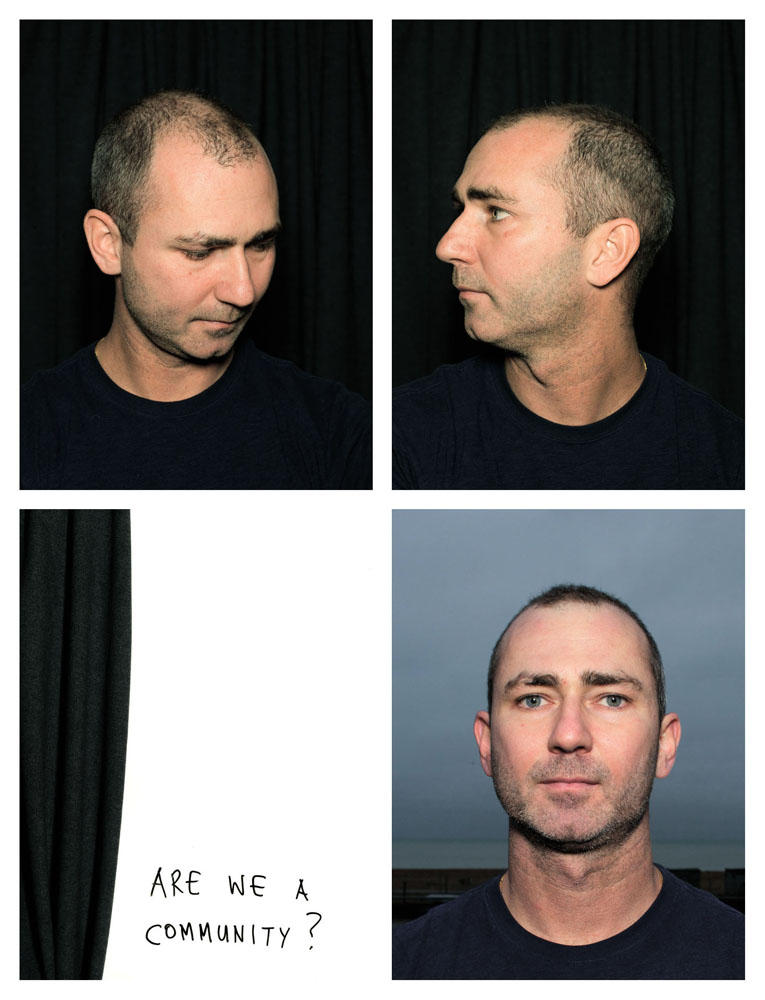

I coined the term 'Assisted Self-Portraits' to give the name to a series of portraits I make with people who have experienced being homeless. In order to make an Assisted Self-Portrait I meet with the participant in locations chosen by them, to teach the individual how to use a 5x4 field camera with a tripod, handheld flashgun, Polaroid and Quickload film stock, and a cable shutter release. The final Assisted Self-Portrait is then edited with the participant. I use the word 'assisted' in order to allude to the collaborative process that underpins the creation of the final image.

Have you ever done a self-portrait of yourself? What was your approach?

In many ways I see my whole practice as a kind of self-portraiture. I'm always attempting to find ways to represent the process of making work about other people and to make the questions I ask myself about photography evident in this work. For example, in my latest body of work called Not Going Shopping, I worked with a group of people living in Brighton & Hove to explore queerness. It seemed an interesting way for me to explore my own views about being queer and at the same time further my inquiry into collaboration.

As part of this work the participants and I created the so-called Collaborative Portraits. I was keen to include a collaborative portrait of myself in this work for, as a gay man, I felt more 'inside' than the work I've made with homeless people, children or Eastern European migrant women. Throughout the process of making Not Going Shopping, a public blog was kept from the first meeting until after the exhibition.

4,000 copies of a 16-page newspaper, containing excerpts from the public blog and our private Facebook discussions, alongside documentation of the making of the Collaborative Portraits, were distributed free across Brighton & Hove. The Collaborative Portraits were also displayed on large-format posters in outdoor public spaces across Brighton. In addition to that, photographs made by participants as well as the Collaborative Portraits are featured alongside excerpts from oral history interviews and ephemera related to the cultural heritage of LGBT people in the Queer in Brighton anthology, which I co-edited with Maria Jastrzebska.

Do you think that in age of the ‘selfie' self-portraiture can still be important and can still say something to us?

Selfies can be a fun way of creating snapshots of ourselves in the midst of experiences that we enjoy to show our friends and family. On the other hand, self-portraiture can be a more considered mode of art-making. I think people will always want to look at other people in photographs and other forms of art making, and self-portraits will hold a distinct appeal and value so long as the work of artists continues to challenge us to consider the threads that form the fabric of society.

Enter our photo contests to win great prizes.

Register on Photocrowd for more great content.