The work of documentary and reportage photographer Stuart Freedman has won many awards and has been published in such magazines as Time, Life and The Sunday Times magazine. In this fascinating interview Stuart discusses the thrills and ethics of his job.

How did you get your start as a photographer?

I came back from the University of Sheffield, where I studied politics and modern history, and got a temporary office job for six months in order to buy some cameras. I started freelancing and built up an (awful) portfolio, but started doing stuff on Sundays for the Times newspaper and magazines like Community Care and City Limits.

After about a year or so I started covering events in Belfast and also Albania as that country opened up. I joined an agency called Select Photos, which at that time was home to, amongst others, Adam Hinton, Dario Mitidieri and James Miller (a friend who would later be killed in Gaza), and pretty soon ended up in the war in Croatia. I started working for magazines like Der Spiegel and Newsweek, covering British politics, but also in the first few years covering stories in Haiti and Afghanistan. I’ve just continued working ever since, but I also now write.

Of all the places you've travelled and photographed, which one had the strongest impact on you?

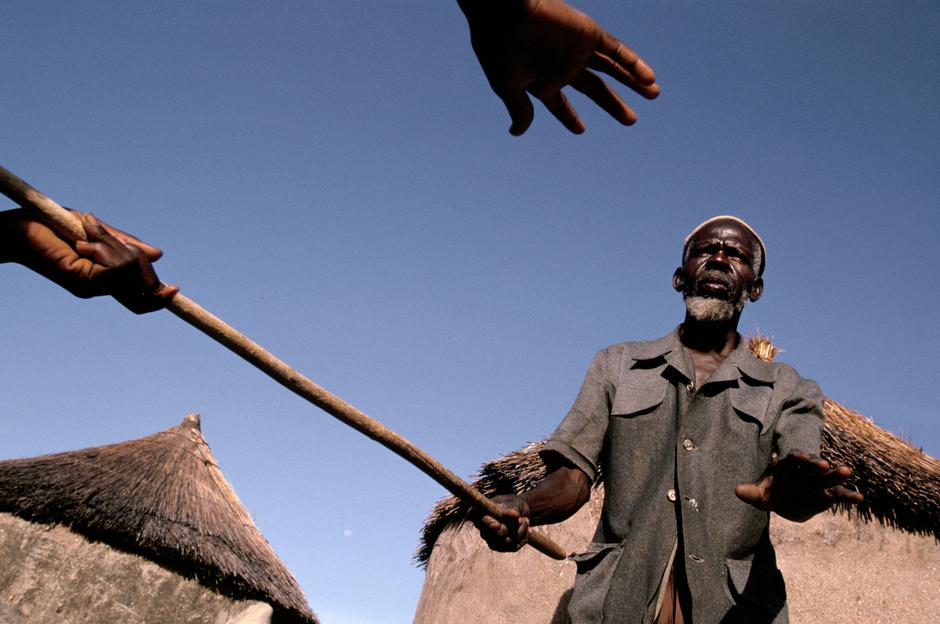

That’s tricky because I can honestly say that so many places have impacted on me. But if I had to choose, there’d be two. Firstly, covering the famine in South Sudan in 1998 was, as one would expect, deeply troubling. Seeing so many people literally waiting to die and being so utterly helpless was terrible, and terrible in the real sense of that word.

Secondly, India. I’ve worked there on and off for nearly twenty years and, unlike many, I have no romantic illusions about the country. I’ve tried very hard not to image it in the innumerable clichés that surround it - mysticism or misery. That said, India has given me a great deal and has taught me a great deal about patience and humility and, I might add, about my own background.

How do you balance capturing photographs against interfering with the subjects?

Generally one has to be careful about just how much one interferes. I no longer cover news and current affairs in difficult places, but the stories that I still do are usually concerned with people in difficult situations. I think that if you are going to stick a camera in someone’s face, you’d better have a pretty good reason to do it. Not for your own ends, not to further your career, but to genuinely try and help. It’s a very difficult equation and on a case-by-case basis it doesn’t get any easier.

That said, I’m pleased to have walked away from certain situations in the last few years, the situations that perhaps I might have photographed a decade ago. However, once you’ve committed to show something, I believe that you should wholeheartedly do so - that’s the reason you’re there. I’m neither a tourist nor a voyeur; I’m a working photographer with an agenda to record what I see.

How emotionally involved with your subjects do you allow yourself to get?

I think it’s impossible not to be emotionally involved at some level with all the stories I’ve covered. One would be less human and certainly a poor journalist if one didn’t. But, as I said before, I’m there to do a job. If I can’t do that job, I shouldn’t be there. I have no business to sniff around people’s misery for fun or for my own experiences. One has to be a professional, and the last thing a person in distress wants is you blubbing with them.

There is an unwritten tacit rule that if you enter someone’s space as a journalist you, act professionally and you act decisively. They know that, you know that - you don’t want to be adding to a difficult situation by making a fuss or a fool of yourself.

Which project are you most proud of?

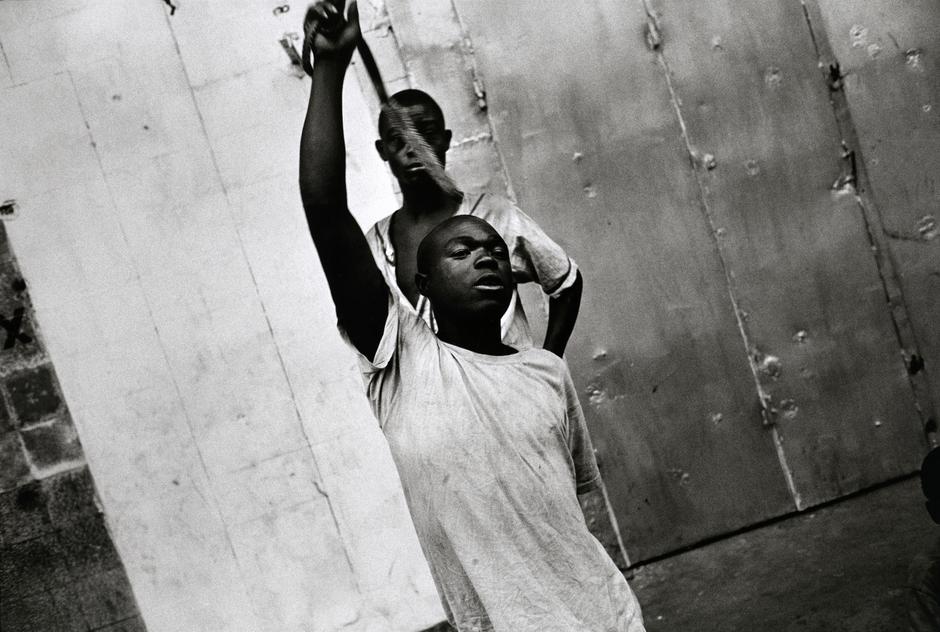

I’m very proud of the work I did in Africa in the late 1990’s looking at violence and young men in Sierra Leone, Liberia, Rwanda, Uganda and Angola. I’m very proud of the intimate work I made in Rwanda in 2004 about people living positively with AIDS. I’m very proud of the work I did with the homeless and mentally ill in New Delhi a couple of years ago, and I’m very proud of the book I’ve been working on for the last couple of years that will be published next year. But I can’t mention more about that at the moment.

Do you have a favourite shot of yours? What’s the story behind it?

I don’t really have a favourite shot, but one that I like (and others seem to as well) is of a chap in Kibileze in Rwanda called Narcisse, who was HIV positive and the president of his local AIDS Association - Girimpuhwe ('Have compassion’). I photographed him praying with his family at home at dawn before they started work in the fields. I remember being in this tiny hut while they were getting ready, just doing what they normally did and then they just stopped and suddenly began to pray by an open window. The space inside the hut was tiny and it was pitch black. The only light was dull and, as I tried to steady myself on my knees I realised I’d have about 30 seconds to make a frame before it was all over.

I was working on slow transparency film pushed to about 400ASA wide open at about a 1/4 of a second on a 35mm Summilux 1.4 on an Leica M6. That was a very quiet camera, but every frame sounded like a gun shot. In total, I made no more than 4 frames and this one was the only one where the baby had its eyes closed. It isn’t of course perfectly sharp but it has lots of things I like. It’s respectful, it’s peaceful and it’s simple. It also says a lot about a really nice man who, despite being very ill, had no choice but to keep working in order to feed himself and his family.

How much gear do you take with you when travelling? What is your most essential piece of kit?

I take as little as I can get away with, to be perfectly honest. It used to be that I could take three cameras, three lenses and a hundred rolls of transparency film on a job - all in the same carry-on bag. These days I have to take a ton of batteries, a surge protector, a laptop and various chargers as well as cameras and lenses. I also take a sensor cleaning kit, numerous phones, a knife, a torch, a lighter. There are lots of essentials. A mosquito net is certainly one, but also good shoes as I walk a great deal. That, and a positive attitude.

Now that everyone has a camera phone, what can a dedicated photographer bring to the world?

I’m glad that lots of people are taking images with camera phones, but the point seems to me to be that professional photographers - certainly professional news and documentary photographers - have to set themselves apart from ‘citizen journalists’. There are serious ethical implications for our written and visual culture when everyone is shouting loudly at the same time without necessarily declaring an interest.

There are constant examples of images that have been faked and staged, and then passed off as news, or lobbying. It’s the same with journalism – there are certain standards for the criteria of truth in our media: balance, fairness, and accuracy of quote. These are not always achieved, but that's the goal. That has to be the same for a photographer and this is an ethical dilemma.

So, for example, it may be that in the absence of a professional journalist, an image from a camera phone may run first. But whose images will the public trust? The veracity of what we as professionals produce should be the defining factor that sets us apart from the herd. Our images should be the trusted ones, analogous to a journalist’s direct quotes. It’s important therefore that when professional visual journalists work, they do so in a way that is mindful of their responsibilities not just to the world, but also their own community. I tread in the footsteps of those that have gone before me and leave a legacy of what I do for the next photographer/journalist. Professional photographers (and journalists) are - and should be - constantly held to scrutiny for the quality and the veracity of their work. It’s how we retain trust in what we do.

Anyone can make a photograph, but the the difference between a professional newsgatherer and a bystander is a code of ethics and an ability to prove sources. A dedicated photographer has to be much more than just an image maker now. He or she has to be a storyteller on many levels, and has to be a photographer, a videographer and sometimes even perhaps a writer – all at the same time. One has to try and bring clarity and understanding through images. More than ever when I’m asked this, I say that it’s essential to simplify visually, because people are bombarded with imagery. It’s the professional photographer’s work that should stand out and shout quality, consistency and accuracy. It’s what I try and hammer into the young photographers that I mentor.

What does your work focus on now?

The same thing that it always focused on – the fact that the world is a beautiful place and full of interesting and engaging stories waiting to be told.

If you could give one piece of advice to an aspiring documentary photographer, what would it be?

There are several, but persistence is the key. I also think Capa’s words about 'breathing the same air as the people you photograph' is very valuable. Only if you experience a little bit of what the people you photograph experience, you’ll make more honest work and, crucially, more intimate work.

Stuart Freedman is now offering a mentoring service to photographers of all abilities, sharing his knowledge of photography to those who want to improve and evolve their work. Find out more about Stuart's mentoring here.

Enter our photo contests to win great prizes.

Register on Photocrowd for more great content.